The Major Arcana of the Tarot: Cards 6-13

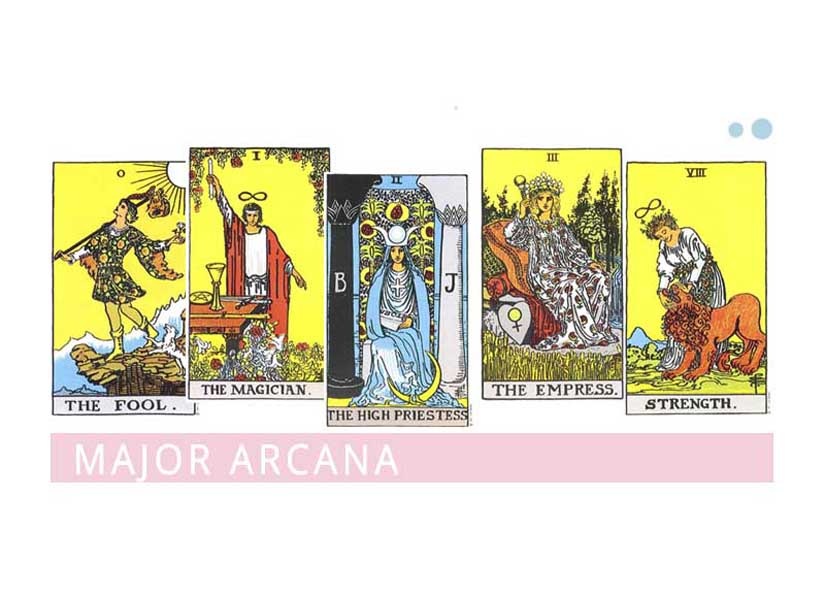

The Lovers. This symbol has undergone many variations, as might be expected from its subject. In the 18-th century form, by which it first became known to the world of archaeological research, it is really a card of married life. It is showing father and mother, with their child placed between them; and the pagan Cupid above, in the act of flying his shaft, is, of course, a misapplied emblem.

The Lovers are of love beginning rather than of love in its fullness, guarding the fruit thereof. The card is said to have been entitled Simulacrum fidei, the symbol of conjugal faith, for which the rainbow as a sign of the covenant would have been a more appropriate concomitant. The figures are also held to have signified Truth, Honor and Love. But we suspect that this was, so to speak, the gloss of a commentator moralizing. It has these, but it has other and higher aspects.

The Chariot. This is represented in some extant codices as being drawn by two sphinxes, and the device is in consonance with the symbolism. But it must not be supposed that such was its original form; the variation was invented to support a particular historical hypothesis. In the eighteenth century white horses were yoked to the car.

As regards its usual name, the lesser stands for the greater. It is really the King in his triumph, typifying, however, the victory which creates kingship as its natural consequence. M. Court de Gebelin said that it was Osiris Triumphing, the conquering sun in spring-time having vanquished the obstacles of winter. We know now that Osiris rising from the dead is not represented by such obvious symbolism. Other animals than horses have also been used to draw the currus triumphalis. It were, for example, a leopard and a lion.

Strength (or Fortitude). The female figure is usually represented as closing the mouth of a lion. In the earlier form which is printed by Court de Gebelin, she is obviously opening it. The first alternative is better symbolically, but either is an instance of strength in its conventional understanding, and conveys the idea of mastery. It has been said that the figure represents organic force, moral force and the principle of all force.

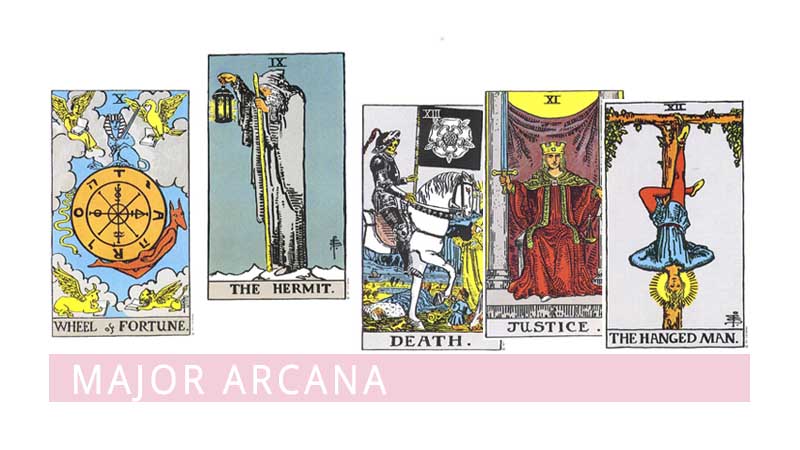

The Hermit, as he is termed in common parlance, stands next on the list. He is also the Capuchin, and in more philosophical language the Sage. He is said to be in search of that Truth which is located far off in the sequence, and of Justice which has preceded him on the way. But this is a card of attainment, as we shall see later, rather than a card of quest. It is said also that his lantern contains the Light of Occult Science and that his staff is a Magic Wand.

These interpretations are comparable in every respect to the divinatory and fortune-telling meanings with which we shall have to deal in their turn. The diabolism of both is that they are true after their own manner. But that they miss all the high things to which the Major Arcana Tarot should be allocated. It is as if a man who knows in his heart that all roads lead to the heights. And that God (Nature) is at the great height of all, should choose the way of perdition or the way of folly as the path of his own attainment.

Eliphas Lévi has allocated this card to Prudence. But in so doing he has been actuated by the wish to fill a gap which would otherwise occur in the symbolism. The four cardinal virtues are necessary to an idealogical sequence like the Trumps Major. But they must not be taken only in that first sense which exists for the use and consolation of him who in these days of halfpenny journalism is called the man in the street.

The Wheel of Fortune. Of recent years this has suffered many fantastic presentations and one hypothetical reconstruction which is suggestive in its symbolism. The wheel has seven radii; in the 18-th century the ascending and descending animals were really of nondescript character. One of them having a human head. At the summit was another monster with the body of an indeterminate beast, wings on shoulders. It carried two wands in its claws.

These are replaced in the reconstruction by a Hermanubis rising with the wheel, a Sphinx couchant at the summit and a Typhon on the descending side. Here is another instance of an invention in support of a hypothesis. But if the latter be set aside the grouping is symbolically correct and can pass as such.

Justice. That the Tarot, though it is of all reasonable antiquity, is not of time immemorial, is shown by this card, which could have been presented in a much more archaic manner. Those, however, who have gifts of discernment in matters of this kind will not need to be told that age is in no sense of the essence of the consideration.

The female figure of the 11-th card is said to be Astrea, who personified the same virtue and is represented by the same symbols. This goddess notwithstanding, and notwithstanding the vulgarian Cupid, the Tarot is not of Roman mythology, or of Greek either. Its presentation of Justice is supposed to be one of the four cardinal virtues included in the sequence of Greater Arcana; but, as it so happens, fourth emblem is wanting, and it became necessary for the commentators to discover it at all costs.

They did what it was possible to do, and yet the laws of research have never succeeded in extricating the missing Persephone under the form of Prudence. Court de Gebelin attempted to solve the difficulty by a tour de force, and believed that he had extracted what he wanted from the symbol of the Hanged Man – wherein he deceived himself.

The Hanged Man. This is the symbol which is supposed to represent Prudence, and Eliphas Lévi says, in his most shallow and plausible manner, that it is the adept bound by his engagements.

The figure of a man is suspended head-downwards from a gibbet, to which he is attached by a rope about one of his ankles. The arms are bound behind him and one leg is crossed over the other. According to another, and indeed the prevailing interpretation, he signifies sacrifice, but all current meanings attributed to this card are cartomancists’ intuitions, apart from any real value, on the symbolical side.

The fortune-tellers of the 18-th century who circulated Tarots, depict a semi-feminine youth in jerkin, poised erect on one foot and loosely attached to a short stake driven into the ground.

Death. The method of presentation is almost invariable, and embodies a bourgeois form of symbolism. The scene is the field of life, and amidst ordinary rank vegetation there are living arms and heads protruding from the ground. One of the heads is crowned, and a skeleton with a great scythe is in the act of mowing it. The transparent and unescapable meaning is death, but the alternatives allocated to the symbol are change and transformation.

Other heads have been swept from their place previously, but it is, in its current and patent meaning, more especially a card of the death of Kings. In the exotic sense it has been said to signify the ascent of the spirit in the divine spheres, creation and destruction, perpetual movement, and so forth.